by JEFFREY COHEN

[cross-posted to In The Middle]

Below, a portion of my introduction to Animal, Vegetable, Mineral: Ethics and Objects. Follow the previous link to read its table of contents. The volume is the first of several to be published through a partnership between GW MEMSI and punctum books. Pleas also consider liking Oliphaunt on Facebook.

Introduction: All Things

Though superseded by a newer translation, Denton Fox and Hermann Pálsson’s version of Grettir’s Saga is a text to which I feel a considerable attachment.[1] Its rendering of the Old Norse narrative is crisp and lucid, capturing the austere yet wry style of the original prose. Even more than its artistry, though, what compels me about the Fox and Pálsson translation is the series of photographs with which the book begins. Between the introduction and the story’s instigation have been inserted twelve poorly reproduced black and white pictures depicting locales mentioned in the saga. Unattributed and unpaginated, this interlude of images captures the multiplicity of histories, real and imagined, that animate the Icelandic narrative and its English reworking: a seeming timelessness in which the landscape is ever as it has been; the ninth through eleventh centuries, when Grettir and his ancestors were supposed to have journeyed these frigid expanses; the early fourteenth century, when the saga’s unknown author dreamt a past that never was and placed its unfolding action at familiar fjords, glaciers, and vales; and the 1970s, when Fox and Pálsson published their English translation of Grettir’s Saga, the first in sixty years. The initial photograph, for example, is labeled “Bjarg in Midfjord, site of Grettir’s birth.” The image depicts an undulation of grass, a lone rock, and a distant mountain — presumably Kaldbak, the chilly ridge that Grettir’s great-grandfather Onund darkly spoke of having traded his Norwegian grain fields to possess. Yet the picture also contains a farmhouse that if not exactly modern is in no way medieval, with its bright paint, three expansive levels, and chimney. The telephone poles and curve of road quietly argue against placing a young Grettir within that home. Yet the story radiates such a keen sense of domestic vitality that it is difficult to resist thinking of this boy destined for a life no farm could contain, creating his particular brand of chaos within that pastoral space. Every time I look at the photo I expect to see geese and a horse, futilely fleeing his juvenile rage; or his beleaguered dad, storming out of the farmhouse after telling a young Grettir one more time that he has made a verybad choice.

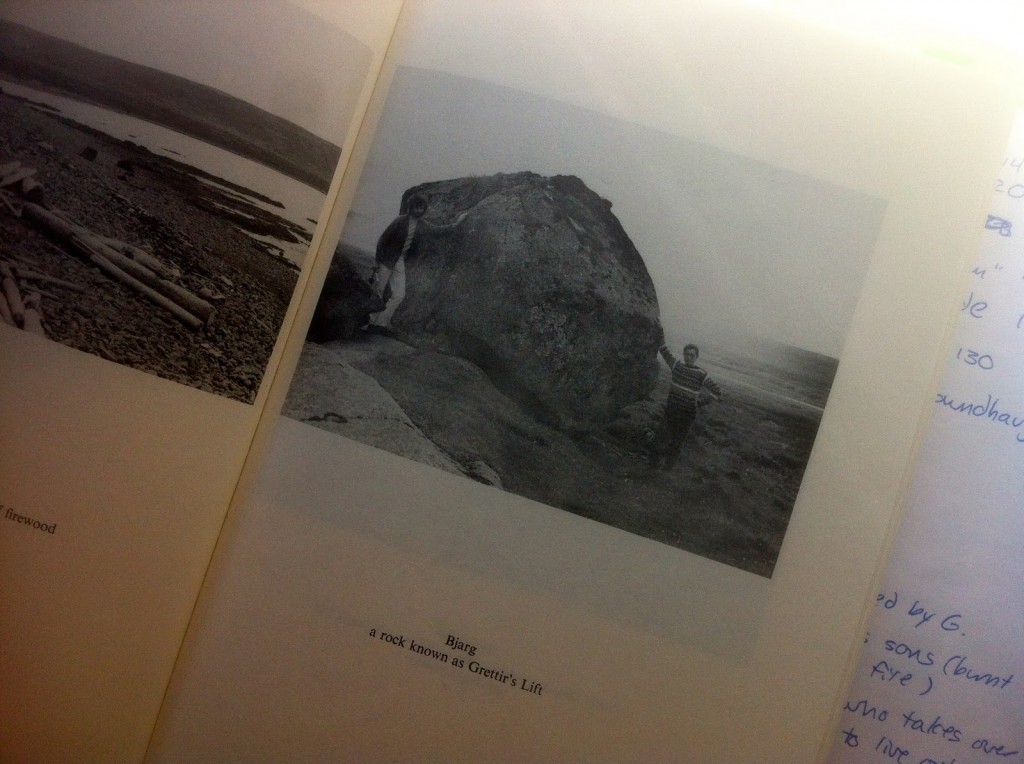

Other photographs in the sequence are less anchored in time and narrative. “Arnarwater Moor, where Grettir supported himself by fishing” has no human content, just rocks and grass and mountains. It’s easy to imagine that nothing has changed here in a millennium. The white snow and dark stone of “Eiriks Glacier” could be as full of half-trolls now as it was when Grettir dwelled in an ice cave, learning for the first time compassion for animals (a grieving ewe rebukes him for the devouring of her lamb) as well as the boredom that comes from a life of monstrous solitude. My favorite image, however, is captioned simply “Bjarg, a rock known as Grettir’s Lift.” A boulder dominates the photograph, looming perhaps nine feet high and twice that wide. A young man stands on either side, each with one hand upon the stone: on the left, a bearded fellow in jeans, a t-shirt and a jacket holding what looks like a small shovel; on the right a man with much shorter hair, glasses, and a wool sweater with a distracting pattern. The exposure for the picture was not well executed, so the image is too bright. It’s difficult to make out details. The first man actually could be holding a camera or a bicycle pump, and the second figure could be a woman. But my best guess is that we have here depicted the two translators of Grettir’s Saga. Having traveled to Iceland together, Denton and Hermann had themselves photographed touching a narrative landmark, a stone so heavy that Grettir alone could raise it.

The boulder christened “Grettir’s Lift” appears twice in the saga. Shortly after his fist Althing ends with condemnation to three years of outlawry abroad, Grettir is journeying with some distinguished men and impresses them with his ability to heft the rock: “everyone thought it remarkable indeed that so young a man could lift the stone” (31). The landmark reappears briefly as Grettir fights haughty Gisli, stripping him slowly of his clothing so that he is reduced to streaking across the landscape in his breeches (125). The stone becomes an immediate and lasting sign of Grettir’s remarkable powers, a piece of the landscape that “still lies there in the grass and is now called Grettir’s Lift” (31). The picture reassures us that to this day we can see and lay hand upon the historical marker. Its endurance reassures us that the saga’s power abides. Denton and Hermann, I imagine, had themselves photographed touching Grettir’s Lift in acknowledgement of Grettir’s saga own impress upon them. The rock takes the place of the narrative, and reassures that some things will never vanish into history, that stories possess an enduring materiality, weighing heavily even when they may have very little that is historical behind them.

The picture of the translators with hands upon the boulder well emblematizes a recurring theme of the saga. Unembellished as its prose may be, the narrative could not progress without a world enmeshed in densely expressive material objects. No matter how firmly anchored they may seem, these objects may, like Grettir’s Lift, suddenly begin to move. Though their power sometimes becomes most evident just at the moment of a human touch, they possess an uncanny agency all their own. Fire, ice and water are actors in the text: they consume, convey, renew, destroy. So is wood. Grettir’s great-grandfather and the man most similar to him sports a timber leg, attached after his limb is severed in battle. The trunk is quite literally Onund Tree Foot’s support, the bestower of his full name. The disability also makes him stronger, more renowned. Early in life Grettir is cruel to animals; toward the end of his days he befriends a lonely ram. Only some of the characters in the saga are people. The short sword that Grettir snatches from the undead Kar the Old becomes his most treasured possession, his constant companion. Kar resided in a dark burial mound, where he sat upon a throne in silent and perpetual surveillance of his silver and gold. Grettir severs the barrow-dweller’s head to end his haunting. He knows that the life of objects is in their circulation, that their consignment to subterranean stasis deprives them of story. Kar’s liberated sword therefore serves him well until his last moments of life. Even in death it cannot be loosed from his hands.

Yet Grettir is also undone by an agential object. Whereas a tree had been the source of Onund’s continued life, Grettir dies when a log on which a curse has been inscribed arrives at his island hideout. His axe rebounds off its trunk and gashes his leg, infecting him incurably. Grettir’s downfall is engineered by a sorceress, a woman who knows how to place the world’s materiality into movement: the enchanted driftwood floats to Grettir’s hideaway against the current, and each time it is tossed into the ocean the log returns. Things matter in this text. And why should they not? Thing comes from a medieval Germanic word denoting a judicial assembly. Thus Grettir’s life revolves around periodic meetings of the Althing, a national convocation of Iceland’s powerful men at which law cases are decided, officials elected, and momentous decisions ratified. This contentious annual assembly held at a place called the Thingvellir was a two week struggle for power. Its participants vied over how best to be heard, how to have an enduring impress, how to bring about a desired future. Here Grettir’s outlawry – his being outside the protection of the law – is twice pronounced. Grettir dies just before he is admitted back into the society that employed the mechanism of the Althing to exile him.

What if at this contest for agency some of those who spoke were not priest-chieftains or influential landholders? What if short swords, enchanted tree trunks, and hefted boulders were allowed a voice? Shouldn’t an Althing include all things? Isn’t a republic a res publica, a public thing? At a parliament (from French parler), who gets to speak? In his book Statues Michel Serres explores the place of things like stones or statues, objects condemned to silent roles in human dramas.[2] Because Germanic and Latinate terms for “thing” are etymologically related to the words for cause (causa, cosa, chose, Ding), Serres observes that things tend to be admitted to reality only by legal tribunals and assemblies – as if reality were a human fabrication (294, 307). Yet things, especially things that appear to hold themselves in silence, must possess a power indifferent to language: something that comes from themselves, not via human allowance. Silent things must be able to speak, exert agency, propel narrative. The philosopher of science Bruno Latour has famously imagined just such a Parliament of Things, where

Natures are present, but with their representatives, scientists who speak in their name. Societies are present, but with the objects that have long been serving as their ballast from time immemorial … The imbroglios and networks that had no place now have the whole place to themselves. They are the ones that have to be represented; it is around them that the Parliament of Things gathers henceforth. ‘It was the stone rejected by the builders that became the keystone’ (Mark 12:10).[3]

Or the stone hefted by the Icelandic warrior doomed to a life of bad luck and unhappiness, a stormy life that proceeded through his dependence upon objects: rocks to lift, swords to keep him company, last days with a fire and a ram and an island and a shepherd’s hut that became his best home.

The essays collected here make a cogent, collective argument that things matter in a double sense: the study of animals, plants, stones and objects can lead us to important new insights about the past and present; and their integrity, power, independence and vibrancy needs to be acknowledged, and can found a politically and ecologically engaged ethics in which the human is not the world’s sole meaning-maker, and never has been.

[1] Grettir’s Saga, trans. Denton Fox and Hermann Pálsson (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1974). Further references by page number. The newer translation is by Jesse Byock (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009). For the saga in Old Norse, see Grettis saga, ed. Örnólfur Thorsson (Reykjavík: Mál og menning, 1994).

[2] Michel Serres, Statues (Paris: François Bourin, 1987).

[3] Brono Latour, We have Never Been Modern, trans. Catherine Porter (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1993) 144.