To pull cities together, and then push them apart. To feel their bricks crumble in our fingers like honeycomb, before fusing them once more between our palms. To hang the great capitals of the world from the crescent moon, like a nightwatchman’s lamp. To fold them into origami birds that nest in our hats and pockets. To unpack them into radiant flotillas that span the placid oceans.

~Dominic Pettman, In Divisible Cities

The Dead Letter Office of punctum books is excited to announce today the launch of Dominic Pettman‘s phanto-cartographical missive IN DIVISIBLE CITIES, a work of incoherent geography and cartographic origami, which we are releasing in a triptych of formats: as open-access PDF text, as print edition, and as a web-book, beautifully designed by Alli Crandell: indivisiblecities.com:

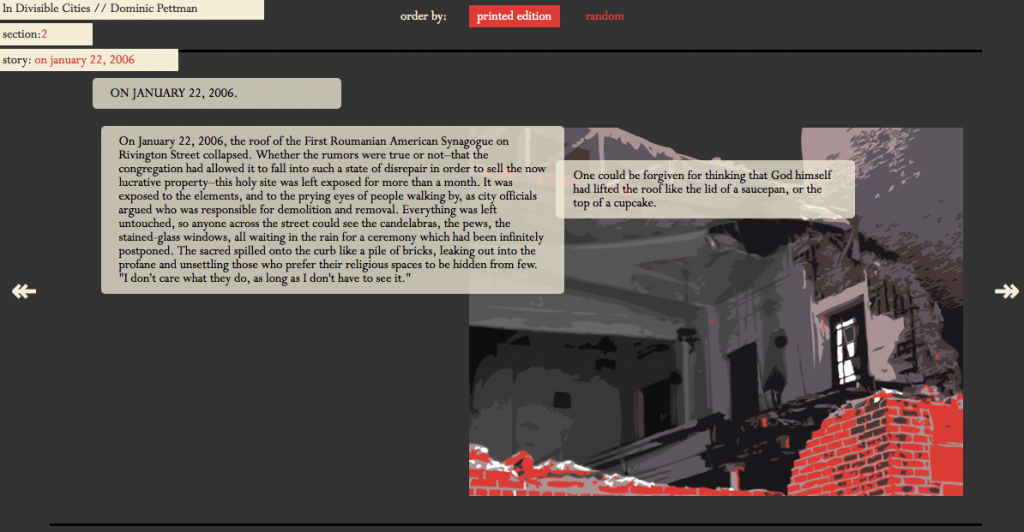

The release of IN DIVISIBLE CITIES represents a massive amount of volunteer labor [especially on the part of the web-designer Alli Crandell, but also including editorial assistants Tim Harvey and Matt Schneider, former students of mine at Southern Illinois University Edwardsville, and Merritt Symes, who contributed the artwork for the print edition], and showcases what is possible with a co-op-style open-access publishing venture such as punctum books that desires to foster author-centered studio-like environments. A book such as IN DIVISIBLE CITIES, which is also an artwork, requires such collective labors because its “clandestine itinerary of hidden affinities, nestled within the habitual rhythm of things” and its Escheresque mapping of an imagined Ecumenoplis requires a certain openness and suppleness of possible “book” and “cartography” formats. The book itself has a certain order [if you believe in page-numbering systems that go in a certain direction, from 1 to 100, and so on], although it can easily be turned to any page and read in random sequences — each separate piece has a certain stand-alone and even gnomic feel, such as:

It’s not uncommon to see “mutton dressed as lamb.” But in Geneva, you often see carcass dressed as mutton. Quite unnerving, really. Clearly this country, dedicated to all things related to the passing of time, has an interesting attitude to the ageing process. Ironic, also, that the Swiss are famous for the clocks and watches that they make in order to measure just how slow time passes in this painfully dull place. Take, for instance, the sign in English affixed to my local hairdresser’s window: “Select a style from our new range of shocking haircuts.” This is funny the first dozen times I pass it on my way to work, but then loses its flavor. When I get to the office, my boss quotes Dostoevsky’s diary: “Been in Geneva a week. The perfect place to commit suicide.”

At the same time, there is a certain double helix [or “Siamese seduction”] between the traveler-narrator and his “romantic shadow” that ties the seemingly disparate fragment mappings together, such as:

In one city we sit face to face on a bullet train, pretending to read. Its velocity such that the world outside has frozen into pure abstraction. Cherry-hued bruises explode and remain, like scientific ink, trapped under glass.

And:

She has returned to my orbit. She is present, but oblique.

Questions are answered politely, but on the diagonal.

She dresses to entice.

Fishnet stockings: a dragnet for the sons of Neptune. (Or should that be Jason?)

Her legs, an academic lesson in “cool Medea.”

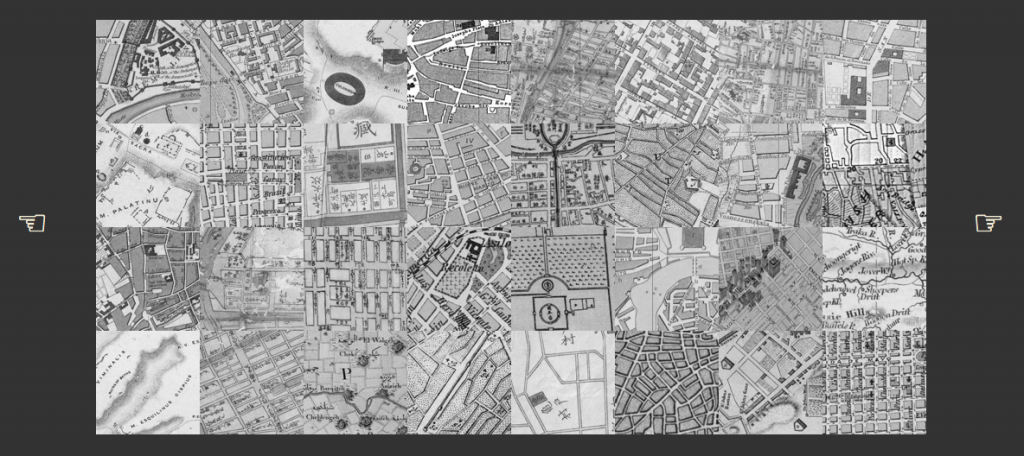

The website, indivisiblecities.com, is divided into 4 origami-architecture-like sections [unlike the book], each of which presents a geometric pastiche of map fragments that can be charted in the same order as the book, or more randomly, creating a gorgeous enlacement of real, lost, and imagined cities, from Brooklyn to Urville to Venice to Peking to Barcelona to Melbourne to Chicago and beyond — all lit with the glow of the narrator’s deft humor — “One is inclined to wonder . . . what the tipping point might be between a large kitchen and a small cutlery museum. Twenty knives? Fifty spoons? Three rare dessert forks?” — and, at times, wistful melancholy: “Emotions, like everything else, become frayed over time. Impassioned commitments lose their vibrant colors, just as the circuits of habit cut deeper and deeper into the heart over time.”

The dreaming of projects such as this one into being requires a lot of creative whimsy, and also a lot of hard work — again, in this case, a lot of unpaid and dedicated, loving labor. It happens to be the case with many academic publishers today — whether commercial, such as Palgrave and Bloomsbury and Routledge, or university-based — that many roadblocks to completely free and open innovation exist, even with those publishers’ best intentions for their authors [it’s a question of money, but also of all sorts of rules and restrictions regarding what is supposedly possible that have simply become lithically intransigent over time]. So, when you go to download the open-access text, or to visit the web-book, please consider making a donation to punctum books:

They can print statistics and count the populations in hundreds of thousands, but to each man a city consists of no more than a few streets, a few houses, a few people. Remove those few and a city exists no longer except as a pain in the memory, like the pain of an amputated leg that is no longer there.

~ Graham Green, Our Man in Havana

Regardless of the amount you contribute, you will be helping to support the open commons — and this means “open,” not just in terms of who has access to the publications, but also “open” in the sense of enabling authors to have access to the means to publish exactly what they want to publish, in whatever styles, forms, modes, etc. they can envision. This is how thought flourishes and also opens up multiple futures [much like Pettman’s phanto-cartography: there is never really a straight line between Point A and Point B and we must have our winding paths and forks in the road]. An open commons is not, and cannot, just be about our ability to get our hands on everyone’s intellectual work for “free,” but must also be about [even, primarily about] opening up the agora of ideas to as many voices as possible, and to as many modes of thinking and doing [because the form of thought matters]. And that requires everyone’s help. That is, if we want this to actually be sustainable. And we do.

One thought on “Incoherent Geography, Phanto-Cartography, and the Open Commons”