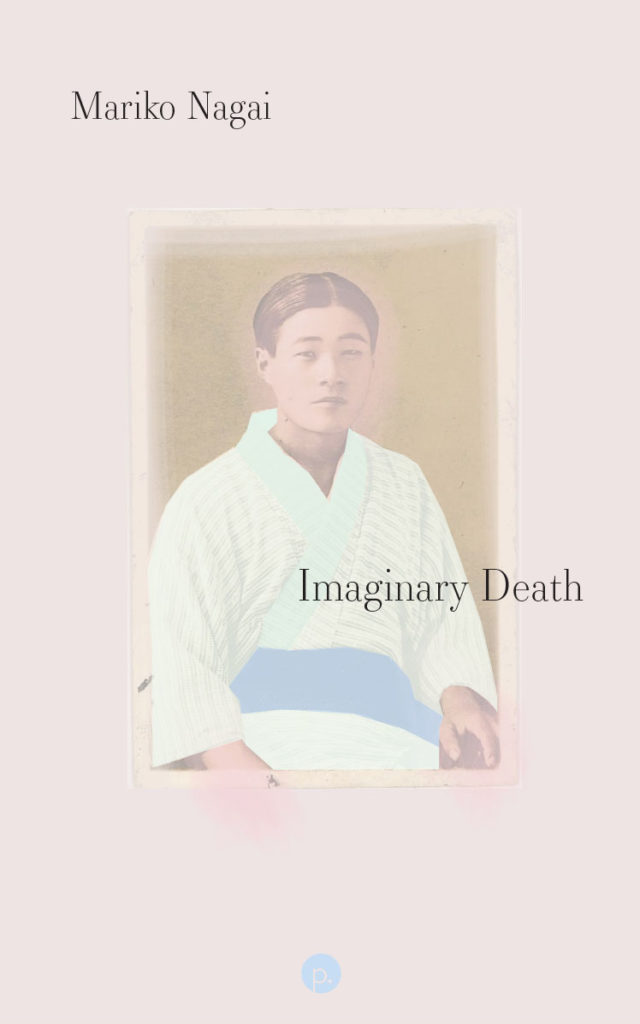

A man dies. He dies because he must—because without his death, there is no story, and, in the end, no history itself.

So begins Mariko Nagai’s Imaginary Death, a creative nonfiction book that examines how the author’s grandfather, an ordinary man born in a small village in the early 20th century, is unmade and remade into a perfect Japanese Imperial Soldier by the era he was born into. In the kaleidoscope composed of archival documents, letters, journals, research, interviews, and photographs, Imaginary Death traces the life of a man who fought and died for the empire, whose death, obscured by lack of documentation, must be composited of many possible ways men could die in Papua New Guinea. Only forty out of four thousand men from the regimental unit survived by the end of the repatriation in 1946: his was one small death out of many.

In the tradition of James Agee and Walker Evans’s seminal work on the Great Depression Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, Imaginary Death is a work that is part meditation, part history, and part fragments of memory that tell a story of a Japanese soldier’s life and death during World War II. Ultimately, Imaginary Death is a textual landscape of imagination, fact, history, and dreams all intersecting to create a psychological terrain that is not limited in the same way as history or nonfiction books, but is rather a new imaginative cartography, no less real than history itself.