In a Trance is just the sort of genre-defying work we at Peanut and punctum and, as it happens, Jeffrey Skoblow, revel in. It is a book-length essay by a fiction writer. It is a fictional essay by a literary scholar. It is a gallant assay by a smart man who thinks while he walks, and he walks a lot.

The book is a meta-meditation on Paleolithic cave drawings and the humans who ponder them. It is fact-based and entrancing just as the cave drawings are actual (existing in time — loosely — and space — more definitively) and mesmerizing. Skoblow is devising stories as “we” (humans) have always devised stories though in a less familiar mode, along a less travelled path.

The essay draws on (!) the careful/thoughtful/whimsical notebooks kept by Skoblow over a dozen years. The notebooks record/illuminate/complicate his visits to twelve Paleolithic art sites as well as his deep, eccentric reading of texts concerned in some way with the subject of cave drawings by an array of scientists, anthropologists, archeologists, art historians, and other sundry enthusiasts and experts, so-called and otherwise.

I saw the caves and didn’t know what to do with them. So I started writing in Spring ’01 to try to figure it out. The first words I wrote were “The caves themselves.” A few pages later: “The caves, no doubt, blah blah blah. To find a way to talk about them: impossible.” It wasn’t going well.

These are one man’s marks made about making marks. Skoblow’s meticulous descriptions attempt the impossible: to provide the “information” that will allow us to see what is visible, invisible, restricted, unseen, hidden, and lost (in the sense of not yet found, or destroyed, or degraded by human presence) beneath the ground at El Castillo and Niaux (for instance). Lines, dots, dashes, body parts, animals, and “hum-animal” figures — things/creatures we have given name to (bison? rhino? vulva? phallus?) in our helplessly homo-sapien-centric attempts to understand (and/or to master our non-understanding).

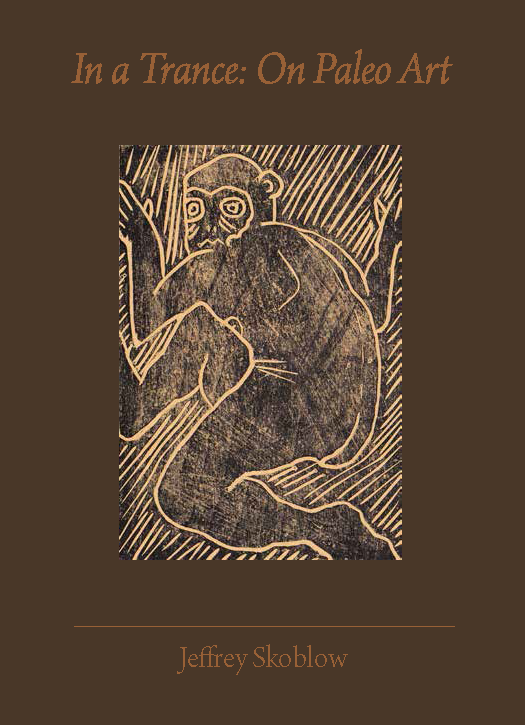

The Great Being would appear to be an androgynous figure, or rather, an ungendered figure almost mistakable for a skull, all the matter of a few deft lines: a slightly crumpled egg-shaped braincase with no representation of hair or other individualizing features, an overlarge eye and a blunt nose, a mouth curving in a long slow grin, maybe, of stupefaction or benediction, benign and spooky all at once.

Here is a leaping mind.

We follow Skoblow as he steps onto an electric train in the caves at Rouffignac and steps out in Southern Illinois, where he cautiously crosses a snake-ridden (maybe) meadow. This is where he meanders further — literally and figuratively: further from the actual caves, furtherest from certainty. These furtherings are exactly what we might expect from a book that from its opening pages declares as one if its themes the difficulties inherent in considering Paleolithic art.

It is problematic … for reasons having to do with the nature of representation and, no doubt, the mysteries of sentient experience. There is also the problem of expectations and intent: to whom does one speak about the caves, and for what purpose?

The pleasures of this book are found in Skoblow’s intense, vigilant exploration of these problems and questions, which are in themselves irresistible. Who are we? In what ways, specifically, and to what degree do we resemble these ancient humans who spray- and brush-painted, smudged, carved, and stenciled images into and onto cave walls and floors and ceilings?