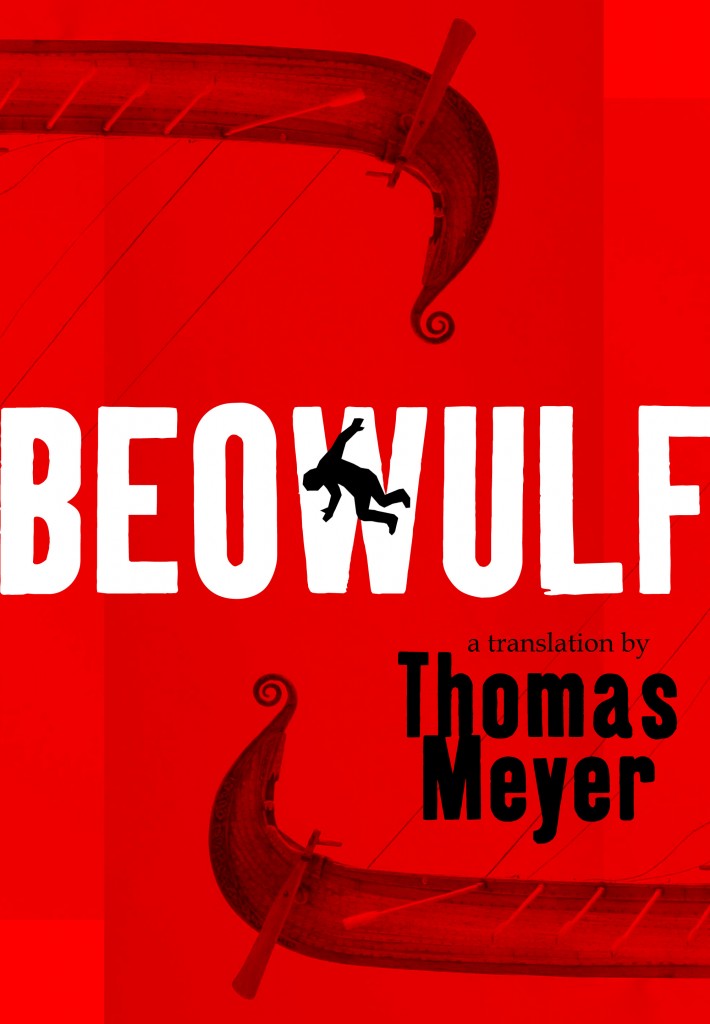

See reviews of Thomas Meyer’s Beowulf: Make Magazine, thecohort@marco, Nomadics, The Medieval Review, H_NGM_N, and Glasgow Review of Books

Many modern Beowulf translations, while excellent in their own ways, suffer from what Kathleen Biddick might call “melancholy” for an oral and aural way of poetic making. By and large, they tend to preserve certain familiar features of Anglo-Saxon verse as it has been constructed by editors, philologists, and translators: the emphasis on caesura and alliteration, with diction and syntax smoothed out for readability. The problem with, and the paradox of this desired outcome, especially as it concerns Anglo-Saxon poetry, is that we are left with a document that translates an entire organizing principle based on oral transmission (and perhaps composition) into a visual, textual realm of writing and reading. The sense of loss or nostalgia for the old form seems a necessary and ever-present shadow over modern Beowulfs.

What happens, however, when a contemporary poet, quite simply, doesn’t bother with any such nostalgia? When the entire organizational apparatus of the poem—instead of being uneasily approximated in modern verse form—is itself translated into a modern organizing principle, i.e., the visual text? This is the approach that poet Thomas Meyer takes; as he writes,

[I]nstead of the text’s orality, perhaps perversely I went for the visual. Deciding to use page layout (recto/ verso) as a unit. Every translation I’d read felt impenetrable to me with its block after block of nearly uniform lines. Among other quirky decisions made in order to open up the text, the project wound up being a kind of typological specimen book for long American poems extant circa 1965. Having variously the “look” of Pound’s Cantos, Williams’ Paterson, or Olson or Zukofsky, occasionally late Eliot, even David Jones.

A glance anywhere in Meyer’s text demonstrates the stunning results. One place he turns it to especially good effect is the fight with Grendel in Fit 11, transforming the famously hyper-condensed syntax of the scene from a discouraging challenge for the translator into a visually pleasing strength:

The eyes of Hygelac’s kin watched the wicked raider

execute his quick attack:

without delay,

snatching his first chance,

a sleeping warrior,

he tore him in two,

chomped muscle, sucked veins’

gushing blood,

gulped down his morsel, the dead man,

chunk by chunk,

hands, feet & all.

& then

footstephandclawfiendreachmanbedquicktrick

beastarmpainclampnewnotknownheartrunflesho

feargetawaygonowrunrun

never before had

sinherd feared anything so.

Here the reader is confronted with the words themselves running together, as if in panic, in much the same way that the original passage seems in such a rush to tell the story of the battle that bodies become confused. This is just one example of the adventurous and provocative angle on Beowulf to which Meyer introduces us. His Beowulf—completed in 1972 but never before published—is sure to stretch readers’ ideas about what is possible in terms of translating Anglo-Saxon poetry, as well as provide new insights on the poem itself.

With a Preface by David Hadbawnik, an Introduction by Daniel C. Remein, and an Interview with Thomas Meyer.

One thought on “Beowulf: A Translation”